EXTREME. ENVIRONMENTS, Fotografie Forum Frankfurt, 24 May - 9 September 2018

Interview with Pradip Malde

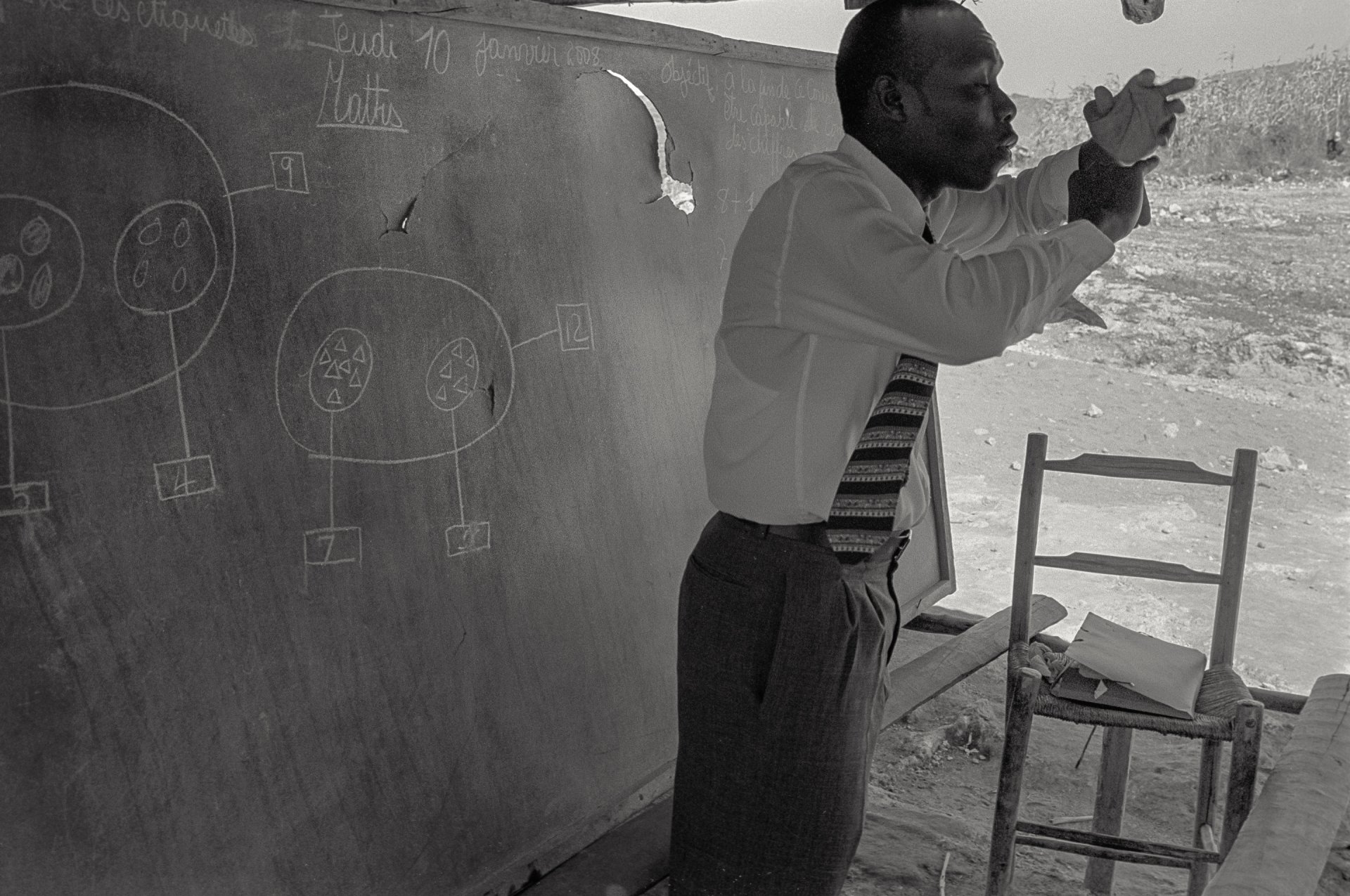

RAY: What was the starting point for your long-term photographic investigation “The Third Heaven” in Haiti?

Pradip Malde: I would like to say this work began the first day I arrived in Haiti in 2006, or to say that it began with an idea about Haiti before my first visit. Yet it’s not as simple or clear as that. The truth is more strange and complex. There seem to be many starting points located far before and much after I began to visit and photograph in Haiti. Two seem more important than others. One of these was from experiences in my childhood, at a time when I did not even know what Haiti was. The other moment of definition was in 2009, when I witnessed a Haitian community mourning the death of a child.

I was born and raised in a small town in Tanzania in the 1960s. The things that filled my childhood with wonder, mystery and magic (playing truant from school so I could watch oil slicks swirling in the local river for example) manifested again in Haiti, but with an important difference: where as a child I connected these experiences to each other through imagination and fantasy, now in Haiti I used the image to understand why wonder and mystery are necessary. The environmental and cultural feel of my childhood and that of Haiti are similar – it makes Haiti a familiar place for me.

I was in Cange, Haiti in 2009. A child had just been brought out of a hospital, having been pronounced dead. A large group of people were outside, many of them very distressed, and I saw a tragedy unfold in this small Haitian market town. A friend explained to me that everyone around the child would soon touch someone else until the entire group was ultimately being touched by someone who was directly touching the child. It astonished me, and I strongly felt that this was the thing that made Haiti special: connections. If I was to make any meaningful (not episodic) work in Haiti, it had to be simple, like this one moment, but layered and complex, as a reflection of how we deal with tragedy and adversity and keep aspiring for love and goodness.

So, The Third Heaven began in my childhood, but the idea of how to structure it came together about halfway through the actual period these photographs were made.

RAY: What does this long term dedication to one photographic project mean to you - do you consider it as a commitment that contrasts with a fleeting with the idea of photojournalism?

PM: A fleeting media picture is something I think of as being episodic. It needs us to agree that somehow, this kind of image is factual, that it stands as evidence of an event. The photographic image is tasked with this because it seems to come from a slice of time, a moment out of a sequence of moments. Time is bonded to fact, and even though we know better, we connect these to truth. We tend to believe that effective photographs are those that render the most significant, the most ‘decisive’ (Henri Cartier Bresson’s essay has fostered far too simple an understanding of photography) moment, out of a sequence of events, and that these relay fact and truth.

With all of this, it is difficult to pack multiple experiences, histories, facts, connections, into single images, into one episode. I even feel that this episodic approach sometimes leads us away from truth, if we think of truth as being amorphous, an ideation, an aspiration. With Haiti, I formed my work around why the place mattered: why was I drawn to it, but more importantly what does it stand for globally? These are complex questions, and need both time and fluidity of approach. What this means is that I have learned to be quiet, and listen and watch; to find seemingly insignificant moments that can actually stand for truth; and how poetry as photography can shape truth.

RAY: Much of your work considers the experience of loss and how it serves as a catalyst for regeneration - what role does photography play in these how do you consider photography as a tool for remembrance and conservation of ephemerality in this context?

PM:

It helps for us to think about identity and the self-as-individual in relation to loss and regeneration. As I work more, I have found myself caring less about self-expression, and more about expression as manifestation of a multitude of identities and selves. I know this sounds crazy, but I am not talking about multiple identities. Rather, that ‘identity’ and ‘self’ are ideas – after all, much of what we understand now about these notions have been shaped over the past 200 years or so – and part of an evolving process.

Experiences of loss, whether they are as constant as the passing of a moment or as traumatic as death, are like moving forward while looking back. We cannot completely let go of the past because it influences how we behave now. A photograph is shaped by what brings the photographer to the present; is born from the moment it is taken; and will both shape and be shaped by the person that looks at the photograph in the future. These dynamics suggest a much more layered expression of identity and self, one that enfolds memory and ephemerality, and also makes conserving these a highly fluid process. Regeneration is a constant, but meditating on the persistent experience of loss, and becoming thoroughly familiar with that experience, seems to facilitate regeneration; letting go without forgetting. It is easier to love with an open hand than with a tight fist.

RAY: Which role does photography in a private or collective culture of commemoration play facing a flood of digital images nowadays?

PM: Implicit in the question is a concern about value and attention. The more common process of looking at a photograph is to look through it, to forget even that it is a surface, an array of marks. John Szarkowsky and others have spoken of this as the ‘photographic window’. And this window, like a magic trick, let’s us believe and commemorate a past, but puts a shroud over what else is actually affecting our responses to the image. A photograph can generate value, or hold ones attention, in other ways than just what ‘happened’ in the frame. It holds value by its optical determinants (sensor, lens, exposure, point-of-view, moment of exposure) as well as by its physical properties (surface, process, tonal values) and for most people, sadly, the effects of these are imperceptible. I strongly believe in process, in making and crafting, because it conditions understanding and meaning in ways that are independent of time and fact. The well crafted photographic image and print play the important role of reminding us to be fully present, to engage in the act of ‘looking with’ as opposed to ‘looking at’. Beauty and love are similar: we choose to be fascinated while agreeing to never completely know; craft allows us to do this.

RAY: How do you relate the documentary (“truth”) and staged (fiction) situations in your work?

PM: I think I address the matter of truth and fiction in the previous comments. Specifically, I think truth is less affiliated to fact and event than it is to belief and agreements, and thus by extension, truth is closer to fiction than we would like to acknowledge. The documentary and staged approaches in photography are zones on the same spectrum. As we talk about light and radio waves being on the electro-magnetic spectrum, I think of truth+fiction or documentary+staged being on the meta-identity spectrum. That is why I think photographers are constantly challenged by ethical and philosophical matters.

What does Extreme mean to you? How do you relate to the topic EXTREME with your own artistic practice? The curatorial team of RAY 2018 states that “extreme is inextricably tied to photography”. Do you agree?

Here too, the question of what EXTREME means to me is addressed with previous responses. I think interstitial spaces are very important. These are, biologically, the spaces between cellular structures. Interstitial spaces support and carry out vital functions for the larger organism. I think the spaces between moments, events, experiences are similarly vital but they are quiet and fleeting. I am most interested in this in-between moment. It can be a bridging point, or transition, or passage. The experience of ‘extreme’ is always relational. Something is an ‘extreme’ only in relation to a normalization of itself, and if the normal and extreme versions are to be used for betterment, I think the interstices between them give us the most wholesome insights about how to proceed. I like to make work that is hopeful, and I look for the moment that is just prior to the extreme.

I think the curatorial team’s statement, “extreme is inextricably tied to photography,” is both visionary and deeply insightful about a little understood and studied aspect of photography. The act of photographing and the act of looking at a photograph oscillates in multiple directions across experience. This experience, being utterly human, is imagination: imagination is: the past; memory; the present; envisioning; becoming reality; the future. These oscillations are at their most energetic, as with all oscillations, at their median points, and are least energetic, or most static, at their extremes. This is why I think that photography is at its most potent when it deals with the in-between states, and why EXTREME is a landmark curatorial statement.

RAY: Do you see boundaries (political, aesthetic, moral, ethic etc.) in imaging the “Extreme” in your own practice?

I do, but only because boundaries are to be approached and transgressed. Otherwise, boundaries are meaningless. However, it is important to consider what the boundaries are. Identity, economic, and environmental boundaries, for instance, define politics, morals and aesthetics. Similarly, my choices, for example of materials such as film, sensors, and printing paper also define political, moral and aesthetic readings and responses to the work. These dynamics are a crucial part of my practice.